When Temperatures Reach 120° F in the Grand Canyon, the Rescue Helicopter is Already in the Air

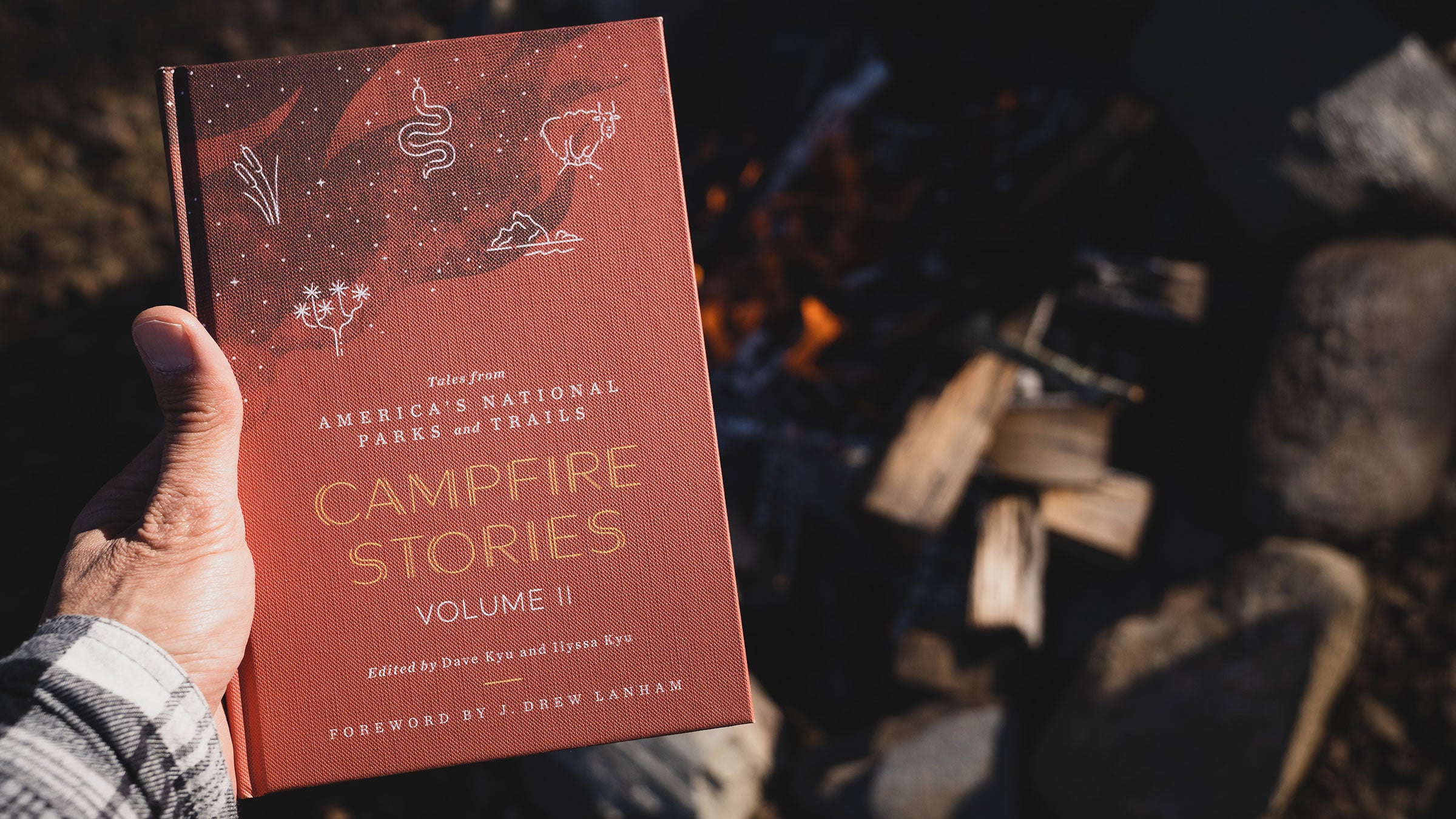

Campfire Stories Volumne II (Photo: by Max Grudzinski courtesy Mountaineers Books)

Inspired by America’s beloved national parks, Campfire Stories Volume II is a collection of modern prose, poetry, folklore, and more, featuring works from a diverse group of writers who share a deep appreciation of the natural world. Award winners such as Lauret Savoy, Rae DelBianco, and Terry Tempest Williams; newer voices including Derick Lugo, Rosette Royale, and Ed Bok Lee; and even a poet laureate, Rena Priest–all share their unique perspectives on our national parks and trails. These new campfire stories revel in each park’s distinct landscape and imaginatively transport the reader to the warm edge of a campfire ring.

The following is an excerpt from CAMPFIRE STORIES VOLUME II: TALES FROM AMERICA’S NATIONAL PARKS AND TRAILS

Chapter: Grand Canyon National Park: A Chasm of the Sublime

Introduction by editors Dave and Ilyssa Kyu

Dave will never live down skipping the Grand Canyon. With two days to travel from the Rocky Mountains in Colorado to Yosemite in California, Ilyssa, who had already seen the canyon, gave Dave a choice: visit the Grand Canyon or stop by Las Vegas. Dave chose… Las Vegas. Let’s just say, some regrets linger.

At that time, we had already visited Great Smoky Mountains and Rocky Mountain National Parks to begin research for volume one of Campfire Stories. For two months, we had been living out of a tent, fueled by sunrises and campfire breakfasts and had a couple more months ahead of us yet, with three more parks to go. Did we need to see another national park? More appealing was the chance to gawk at neon lights and spend a night in a Gothic art–themed hotel and nightclub. More importantly, the immensity of the Grand Canyon loomed in Dave’s imagination. For the parks on our research trip, we planned to spend at least two weeks in each: to visit both the popular and less crowded places, to speak with the people that champion these parks, and really let our bodies soak them in. The prospect of adding six hours to our route, only to stand at the North Rim for one, maybe two hours, just didn’t feel like a visit that could possibly do justice to a canyon that’s been named one of the seven natural wonders of the world.

Here in the Grand Canyon, we witness the forces of rock, wind, and water working in tandem to create a natural wonder of the world. Time on the scale of the geologic requires us to rethink our own sense of time. To understand how the canyon came to be, the National Park Service (very helpfully) asks you to remember DUDE: Deposition, Uplift, Downcutting, and Erosion. First is Deposition, in which igneous and metamorphic rock was gradually covered by layers and layers and layers (deposits) of sedimentary rock. Remember that the oldest rocks in the canyon are 1.8 billion years old. The youngest? The Kaibab rock, at 270 million years. Next is Uplift, grinding tectonic plates that lifted those rocks high and flat, creating a plateau. Then come Downcutting and Erosion, which is where our Colorado River comes in. When the river flooded, its fast current and large volume of water carved away at the rock to create a channel, which was further eroded by weather, wind, and rocks carried by the river. In an arid landscape, exposed rock is weathered and susceptible to deeply dramatic carvings, like say, a grand canyon.

The beauty of this place also conceals extreme danger. For as lush as the river seems and as awe- inspiring as the views can be, this is still an unforgiving desert landscape. Many take on the canyon with exuberance, descending into the gorge to test their limits, without realizing the difficulty of the return trip. And in the age of the camera phone, one misstep while staging the perfect selfie at the canyon’s rim may lead to injury or death. Between 2018 and 2020, there were a reported 785 search and rescue incidents in the Grand Canyon. An author in this collection, Mary Emerick, worked as a search and rescue ranger there one summer. “I went thinking I was going to fight fires,” she recalled. “Instead, I picked up the dead and dying from the canyon’s blazing interior—the foolish, the unprepared, and the plain unlucky.”

From the safety of wherever you’re reading, enjoy this tale from Grand Canyon National Park.

Rescue Below the Rim

by Mary Emerick

When I arrive at the Grand Canyon helibase, the air is still deliciously cool. It is easy to believe that today will not be like yesterday. Today I won’t end up a bystander to someone’s tragedy. The rescue helicopter will stay at the base instead of dipping below the Abyss to hover along the Tonto plateau, searching for hikers in distress. Nobody will fall out of a raft into the Colorado River. Someone won’t die today. I want to believe this even though none of the days preceding this one have borne this out to be true.

It is June, when nobody should hike below the rim, but everyone does.

The four of us on the helicopter crew scatter to do the busywork that keeps us occupied until the paramedics arrive: inventorying supplies, pulling weeds, eyeing the clock. Before noon, even here on the South Rim at seven thousand feet, the temperature ticks toward eighty. Below us in the canyon’s yawning mouth, it is much hotter, spiraling over one hundred degrees. It won’t be long, I think, and it isn’t. I hear our foreman, Mike, fielding a radio call: female hiker, unresponsive, likely hyponatremia, Bright Angel Trail below Three Mile Resthouse. Within five minutes the medics show up, two unsmiling men in flight suits. They spare no greetings; there isn’t time for that. Besides, we will see them half a dozen times before our shift ends.

They tell us what they need and I gather the equipment. What they will find is unknown. The rescue information is sometimes passed on by other hikers, second- and thirdhand, so we have to guess. The helicopter is configured according to each mission. If we need a stretcher, the seats are taken out; if the doors need to be off for a short haul, we remove them. I have practiced this in drills, and I know what to do. Everything is preweighed, so I scribble each item down on the pad I carry and add the weights up to ensure we are all right to lift off. I double-check my math; a mistake, loading the helicopter too heavy, could be disaster. The mood crackles through the base, a controlled urgency. Minutes could mean the difference between life and death. I feel the familiar knot of worry in my stomach: Have I missed something? Helicopters have crashed before in the sullen heat of the canyon.

Before I came to the Grand Canyon, I believed everyone could be rescued. I believed this despite evidence to the contrary. In Idaho, I helped search for a little girl who vanished as she walked home on a dark small-town night. She was never found. But most of the rescue missions I had been on resulted in success: a horseback rider with a broken pelvis carried out on a stretcher, hikers bandaged up and sent on their way. As a wilderness ranger, I carry lifesaving equipment in my backpack. I want to believe in rescue. The canyon is teaching me otherwise.

It is my turn to fly so I vault into the right front seat beside Eddie, the pilot, and we lift off from the cracked concrete as I settle the flight helmet on my head. I study the coordinates while Eddie relays our position to dispatch. The rest of the crew watches until we clear the base, then go back to their chores. They know they will be next.

Imagine this: You sit sweating in a sticky flight suit, zipped up to the throat, looking through the bubble of the helicopter’s windshield. The thump of the main rotor mirrors your heartbeat. A mix of adrenaline and fear rockets through your veins. Below your feet, separated only by fragile layers of composite aluminum and stainless steel, is the wide expanse of the canyon, terraces and plateaus like giant steps down to the serpentine blue of the Colorado River. This is as close to flying as you will ever get, and as far from safety as you will ever know.

When hikers descend into the Grand Canyon in summer, they are walking into the mouth of the dragon. The canyon breathes like a pair of lungs, exhaling superheated air. The deeper a person drops toward the river, the hotter it gets. In winter, when the South Rim is buffeted by winter storms, it is possible to sit on the boater’s beach near Phantom Ranch in shorts. The canyon feels gentle then, friendly even. Not so in summer.

We pass through the layers of time, the remnants of an ancient sea. I register each by its color: Coconino sandstone, a chalky, crumbly white; Redwall limestone the color of its name, a deep blush. The Grand Canyon is a multilayer cake, each section a story. Some days, on rescue missions, we descend through them all.

Eddie hovers the helicopter over the Bright Angel trail. I scan the horizon for threats: other aircraft, even hikers wanting to be helpful but ending up in the way. We are just above Havasupai Gardens, above the cottonwoods, before the trail steepens for the climb home. I lean out from my side, watching as we inch toward the ground. My job is to decide if it is okay to set down the skids. A mistake could be costly: damage to the helicopter or even a flip. “Looks fine,” I say into my mike, and he lowers the helicopter all the way down. At his nod, the paramedics and I spring from the ship, heads low to avoid the spinning rotor. We will be loading hot today, the helicopter still running, in a desperate bid to save a life.

A woman is lying on the ground, her boots dusted with red limestone. She is still, not moving. Her pack is abandoned by the side of the trail. A day hiker. I avert my eyes. It is too easy to be drawn in, and I have already learned that I can’t be invested in the outcome. I have to shove all of my emotions down deep, where they can’t prevent me from doing my job. I need to let the paramedics work while I deal with the husband. He is distraught; they always are.

“Is she going to be all right? We were just hiking, she was fine,” he says, climbing into the extra flight suit I brought along and not protesting. The partners of the ones we rescue are combative sometimes, but he seems dazed and compliant. I have no answers as I lead him to the helicopter and the patient is loaded in on the backboard. He is lucky, though he wouldn’t believe it right now. Sometimes we don’t have room for the rest of the party and they have to hike up, all the way alone, past the resthouses and the happy people coming down. Nobody can hike fast enough to escape their thoughts.

Another name for hyponatremia is water intoxication, as if you are drunk on water. And you are, your body bursting with water but dry of electrolytes. People at this stage act intoxicated, wobbling and stumbling. They laugh. They don’t realize the danger. It can progress quickly, as it has with this woman. The stage past intubation, a tube shoved down her throat to help her breathe, can be coma and death.

We lift off quickly. Eddie’s face is inscrutable. He has been at this for a long time, and nothing rattles him. He points out the remains of a car embedded in the top layer, Kaibab limestone. An accident? Purposeful? I never learn. But there it is again: someone who could not be rescued.

The husband and I are left unceremoniously at the helibase. He will have to drive to Flagstaff while the helicopter takes his wife to the hospital there. He lingers for a moment, confusion written over his face. How could a simple day hike have turned into someone fighting for her life?

I want to tell him that I don’t understand it either, that before I came here, I thought of wilderness differently. Always working in alpine environments, I know about lightning and bears and creeks running high with snowmelt. If you’re prepared with the right tools, you can usually save yourself from a tragic fate. But this place, stark and beautiful and indifferent, draws people in. The corridor trails lure them to go just a little bit farther. I have seen these people, in flip-flops and carrying a half liter of water. Before they know it, they are two thousand feet below the rim and have to climb back out.

I think uneasily that this man probably shouldn’t be driving the eighty high-desert miles to Flagstaff by himself, but none of us can leave the base. More rescues are being called in and I see one of the crew grabbing a flight helmet. The man leaves, finally. I have never learned his name. I will never know if she lives or dies, though the scale is not tipped toward survival. The helibase is set far back enough from the tourist routes along the rim that there may as well not even be a canyon. But I know better. I can feel its presence. In my mind I can see the trails, red dust rising as I hike, a slender ribbon of river seen far above, a seduction. Soon there will be another call, someone wavering between life and death.

Or it could go this way, and it has: someone fakes an injury to avoid hiking out, or has bitten off more hike than they can chew, and the rim, far above, feels too daunting to reach. When this happens, we hope the rangers have convinced the person to take a breather, wait it out, and gather courage. Flying in the canyon is tenuous at best, sandwiched between walls that narrow down dramatically, our shadow a small bubble on the sun-filtered canyon walls. I have been taught to evaluate the mission before we lift off. Is it worth risking the lives of the crew? We can’t rescue everyone.

I am only here to fill in for two weeks before going back north to my regular wilderness job. The rest of the crew is here for the long haul, with three more scorching months to get through. They hunch on their heels passing the time. Malcolm, my favorite because he is soft-spoken and not as hardened as the others, retreats to smoke cigarettes in the narrow shade of the sloping roof. Some of the others play hacky sack. They talk about anything but what we are doing, wiping their minds blank between each mission. I have not yet learned how to do this. The faces of those we have saved, or not, linger.

The next day we respond to a river accident. A raft has wrapped around a rock in Hance Rapids, and we have to get the crew off the water. The rangers work quickly to pull short-haul net screamer suits on the passengers, and one ranger and one tourist fly entwined underneath the helicopter from raft to beach. I stand there to direct the passengers to a safe location. Every time someone is offloaded, the rotor wash creates a tornado of sand that settles deep into my skin and teeth. At night in my room, I scrub ineffectually at the dust left behind. It won’t completely wash off. I think that the canyon is settling into my bones.

When it is time for me to leave this short-term assignment, the rest of the crew barely acknowledges my departure. They look up briefly from their chores, but I know that it isn’t personal. Malcolm is already gone; he has decided to leave the crew. The constant edge he has to walk in order to do this job has burned him out. The others suit up. The helicopter is already firing up and they have work to do.

Years later I hike in the canyon solo. The heat presses down, an invisible hand, as I walk across Furnace Flats to Tanner Beach. The sun is a hostile beam. It is high noon, and I am the only creature moving in this harsh place.

I am carrying four liters, way too much water for this nine-mile hike, and I think about water intoxication as I pause to drink. I am thirsty but not hungry, the classic setup for hyponatremia. Pulling out my food bag, I force down some trail mix, the salt from peanuts sharp on my tongue. When I reach the Colorado, I fling myself into water so cold it makes me breathless. It is only April and nearly one hundred degrees. Later that year a woman dies on the Tonto plateau; a man ascending the South Kaibab Trail also succumbs to the heat. In the years since I worked on the rescue crew, nothing has changed.

The next day I hike on the exposed, crumbling edges of the Beamer Trail, five hundred feet above the river. There is no room for error here, and I haven’t seen anyone since I left Tanner Beach. But the farther I hike, the more the canyon opens its arms into a welcoming embrace. I am a feral creature, sleeping in the sand, hair tangled, river water drying on my skin. I learn why people attempt to know the canyon. It is worth the risk.

Climbing out the Tanner Trail four days later, I come upon several hikers who underestimated the descent. They sit along the trail like wilted flowers. “How much farther?” they ask. They point at the watchtower, visible for miles. “We must be halfway,” they say, when they aren’t. Some are forced to bivouac partway down, the river in view but unreachable.

I can’t do much except encourage them. They are too far down the trail to get back out before nightfall. There is scarce shade. Rest, I say, eat something. You are almost there.

I hope they make it. I know now that everyone cannot be rescued. We all do what we can.

About Mary Emerick and This Story

Mary Emerick is the author of the novel The Geography of Water and two memoirs, Fire in the Heart and The Last Layer of the Ocean. She lives in a log cabin in eastern Oregon and spends all of her free time in the mountains.

Mary Emerick has spent most of her life traveling and moving back and forth across the country working for the National Park Service and the Forest Service—fighting wildfires, giving cave tours, planting trees, conducting wilderness patrols, and leading kayak ranger programs. In 2000, she went to Grand Canyon National Park to help rescue personnel who were shorthanded during a particularly dangerous June.

As she describes it, “I went thinking I was going to fight fires, the only reason, I thought, for existence; I was in love with firefighting and the person I was on the fire line. Instead, I picked up the dead and dying from the canyon’s blazing interior—the foolish, the unprepared, and the plain unlucky. During that time, I came face-to-face with mortality and risk in a way I had never experienced before. Wilderness, I had always known, was indifferent, but here, it was also unforgiving. At a time when I was trying to figure out my life, single and independent, it showed me the value of having someone to pick you up and, perhaps, save your life.”

Grand Canyon has the most search and rescue operations of any national park, with a reported 785 incidents between 2018 and 2020. Many of these—most commonly falls, heat stroke, and dehydration—emphasize the importance of being prepared for the elements, and staying humble in the canyon.

Excerpted and adapted from CAMPFIRE STORIES VOLUME II: TALES FROM AMERICA’S NATIONAL PARKS AND TRAILS edited by Dave Kyu and Ilyssa Kyu (April 2023). Published by Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved. Used with permission from the publisher. Buy the book at Bookshop.org or Amazon.com.